- Views676

- Likes3

Siapa Cacat?: A Disabled-led Theatre Production

Five Arts Centre, GMBB, KL

Produced by Teater Untuk Semua, in collaboration with Five Arts Centre

22 & 23 November 2025

Review by Leow Puay Tin

Teater Untuk Semua is a new theatre company. It recently staged its first public production at the Five Arts Centre studio in the GMBB art mall in a gentrified part of Pudu. Called Siapa Cacat?, the production challenged the insidious belief that people who have been labelled by the state and society as ‘orang kurang upaya’ – literally ‘persons with less capability’ – are disabled in all aspects of their life, and therefore always in need of charity and protection.

So Siapa Cacat? was not just a theatre production. It was also a project. As stated in the programme book, “Siapa Cacat? is a Disabled-led theatre production, created, produced, and performed by a new collective of Deaf, Disabled, and neurodivergent creators under Teater Untuk Semua. The title reclaims the word ‘cacat’ – often used as a slur – as a statement of empowerment and a provocation to rethink who belongs on stage.”

Having gone to see it without knowing what to expect, after listening to snatches of an interview on BFM Radio with the two neurodivergent directors, Ho Lee Ching and Jazzie Lee Jin Jye, I came away moved and elated. In seeking empowerment and provocation, I felt that Teater Untuk Semua had created an exhilarating and ground-breaking theatre production.

In terms of structure, the performance began and ended with the external world that persons with disability share with the rest of the population. In between were their unique perspectives of this shared world as experienced by them.

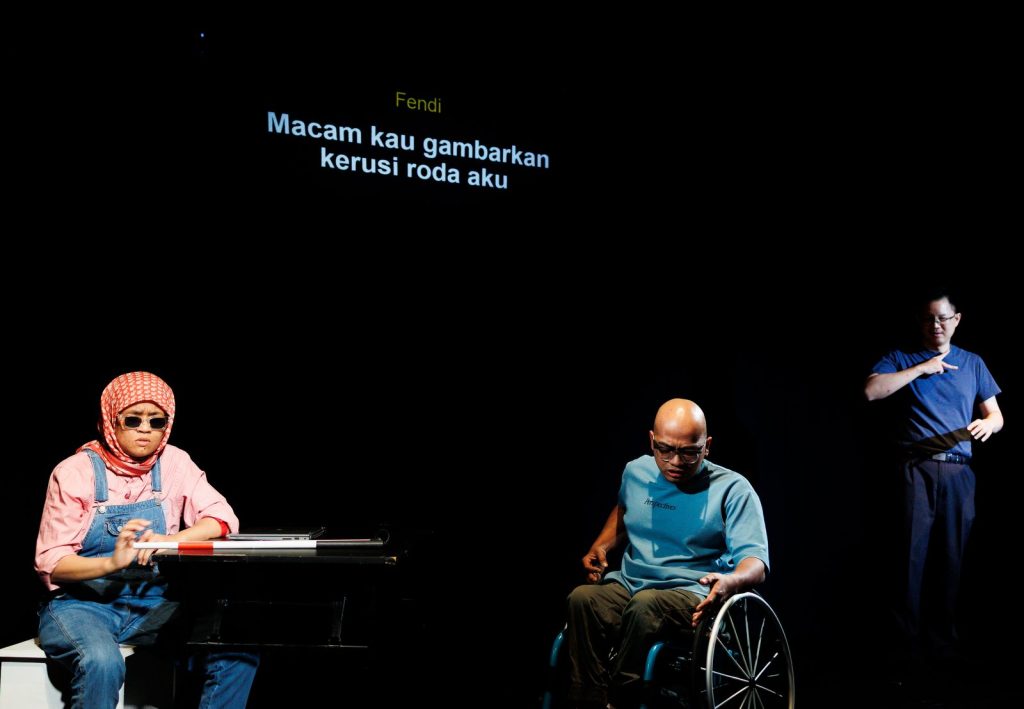

Because of the actors’ various abilities and disabilities (some of which were not obvious), their performance was presented through a rich variety of modes and genres and styles. This diversity was augmented onstage by an interpreter for the deaf (Aw Wei Chun) ‘performing’ a parallel performance using Malaysian Sign Language interpretation in full view of the audience. There was also an unseen interpreter for the blind (Nephi Shaine William), who was watching a livestream of the stage on a TV screen in a room nearby and speaking her audio descriptions into the headphones of audience members who could not see. And then, there were the surtitles projected on the back wall.

How did the production team ever manage to work out the minutia of how and when to translate what? But they did. And it worked! In short, Siapa Cacat? was highly stimulating and kept you on the edge of your seat.

The premise of Siapa Cacat was simple but effective. A group of eight people had come to a bus stop to wait for a special-access bus. When it didn’t turn up as scheduled, they began to make friends with one another and share stories. This went on for a bit longer than expected because when the bus did show up at some point, it didn’t/wouldn’t stop despite their frantic waving and shouting, forcing them to wait for the next bus.

The takedown of cliches and stereotyping started early in the performance, with satire. A woman came in with a companion, to wait for a bus by the side of the road. She was sipping now and then from a takeaway coffee cup. A random guy came along, took one look at her white stick and dark glasses, quickly popped a ringgit note into her cup and ran off. When her friend alerted her to what had just happened, Ameera (played by Ameera Ramlee) threw a fit. For not only was her coffee ruined, she had been treated as a beggar, yet again, just because she was blind in public.

[A note: Because the actors were using their real first names in the show, it is natural to assume that the material they performed was autobiographical or that they were performing themselves. But they had made no claims to either, and since representation is the core business of the theatre, I will be referring to the people who appeared on stage as characters, played by actors whose first names they shared.]

The project to provoke and change mind-sets towards disability was more subtly and differently done in the rest of the show, but almost always with humour. At one point, the dismantling of cliches and stereotyping escalated into standup comedy, where call-outs and insults came in a rapid fire. Often, however, the dismantling didn’t involve confrontations or refutations at all. The people and their stories were presented, in medias res, without backstories or explanations and this underscored the representational effect of their presence.

While waiting for the bus, the people took turns to share a story with the others, and this became a ‘show(case) within a show’ that formed the main body of Siapa Cacat?, sandwiched between the opening and closing scenes.

The different pieces in the showcase were not linked by cause-and-effect or even thematically. But phenomenologically, they were similar in their authenticity as fractals of lived experiences and insider knowledge. The overall effect was one coherent, variegated, multi-faceted, collaged text which was executed as stand-alone acts.

The showcase began with a moment-by-moment account of a man’s larger-than-life abdominal surgery-butchery performed (by Dino N. Hassan) through graphic mime and a few key words that was in equal parts hilarious and excruciating.

He was followed by a visibly pregnant woman (performed by Sharifah Nur Jahan) who described the images and sensations of the sea that she could see and feel in her dreams that harkened back to a time when she could still see. Jahan spoke of a wish to see the face of her baby, a dream that would remain unfulfilled, and the judgement of people who thought it irresponsible of someone like her to bear a child.

After her came the stand-up comedian (played by Lavinia A.) who was stunningly articulate and sharp in her observations and critique of human behaviours towards the OKU, from the point of view of a deaf OKU. To pick one instance from her set: she was outraged that some stupid young people her age (20-somethings) thought it was okay for them to take over the only available OKU parking space in a crowded night spot and use it for their private party, since OKUs went to bed early and it was past midnight. And besides, no OKU would ever come to a hedonistic place like this to drink and hang out or make out. They were “pure”, innocent, friendless, sexless. It was thrilling to watch her taking an instance of bad behaviour and chasing it down to its roots, to expose the ignorance, infantilisation and rationalizations at source. She went further to rock the audience with outrageous jokes on sex and the ‘perks’ of being deaf in sexual encounters with callous men — with a passing lament about the high price of vibrators. It was a class act.

A woman wearing noise-cancellation headphones throughout the show (played by Nuna Wan) had been keeping Ameera company on the sidelines, updating her on things happening on stage that she couldn’t see. Nuna used her turn to perform an internal monologue naming the objects in her bedroom over and over. What’s happening? A panic attack? A mental breakdown? As she struggled to calm down, the other characters rallied behind her, intoning “nafas, nafas, nafas” as they breathed in unison with her. The sudden coming together as an ensemble was unexpected and dramatic as a moment of spontaneous empathy and support.

After the ensemble was a poem that was created sensorily (by Gejaletchumi Murugaya) using only body movement, gestures and facial expressions to express her awe and delight at the sight and feel of rain and wind. Hers was the only piece that had an additional accompaniment of music, something which she probably couldn’t hear and which distracted me because I could. Maybe selfishly, I just wanted to see her performing the poem without add-ons, because I could see?

The poem was followed by a song of being in love, performed karaoke-style by a young woman (played by Nur Aisyah Shahimee) who didn’t or couldn’t keep up with the taped music that was running on mechanically rather than accompanying her. It reminded me of myself at the karaoke. But unlike me, she loved what she was doing and had great style.

The last act in the showcase was a scene between a character Fendi (played by Fendirocka Notapurba) confronting the writer who had created him (played by Ameera Ramlee). It used dramatic dialogue to ask troubling existential questions about the purpose of life and human agency. Why, he asked his creator, did she make him cacat? As the author, could she not unmake him? Why not? How then could he change his fate? Was a change even possible? The scene closed without a satisfying answer from his creator, who was herself blind.

When the showcase ended with Fendi’s question about the possibility of change still hanging in the air, the bus still hadn’t come. The waiting had become too much by then. The collective patience gave way to a wordless restlessness and soon people began to leave the bus stop. They had given up. The bus would never come. The public transport they had been waiting for suddenly became symbolic of their unspoken hopes and expectations of the external world which had let them down, yet again. The mood had turned sombre.

Now, in a repeat of the opening scene, only two people were left on the stage: Ameera and her sighted companion. It was back to the beginning for them. Despite the erstwhile esprit de corps, nothing had essentially changed for them. Disappointed, like the others who had left, her companion too wanted to leave and to take her along. But Ameera’s response was a surprise and a revelation: Let’s wait another five minutes. And at that, the sombre mood lifted, even as the stage lights faded out to black. Those words were dramatically very powerful. By giving the special-access bus another chance, she was giving hope and the future a chance. With her determination to hold out for something she wanted, Ameera, who had the last line in the show, reinvigorated the project of Siapa Cacat? to bring about change through the medium of the theatre.

It was an elegant and profound ending to a thought-provoking production about disability and also the theatre itself. In creating a performance with and by individuals with physical disability and neurodivergent conditions, Teater Untuk Semua had produced an excellent new work that was endearingly spontaneous in tone and yet disciplined and tight in its performance. The curation and direction of the performance text were sensitive and sure-handed in hooking the audience right from the start and keeping them engaged without a break for 80 minutes, through humour, insights and authenticity.

Teater Untuk Semua may also be on the way to developing a new kind of inclusive theatre if it could continue to explore ‘translation’ in/as performance as a means of making ‘people accessible to people’. For me, its non-stop, massive use of ‘translation’ was not only innovative but impressive for another reason. Without making a fuss or calling attention to the fact, it had bypassed the persistent segregation of our theatre-making and theatre-going by language, race/ethnicity, economic class. Siapa Cacat? was truly a capacious ‘theater untuk semua’.

Go and catch Siapa Cacat? when it gets staged again, as it must. It has been made for you, whoever you happen to be.

Thanks to Transhallow for all photos.

Leow Puay Tin is a playwright, text curator and performance-maker.