- Views213

- Likes2

Fragments of Tuah

Five Arts Centre

GMBB Kuala Lumpur

28-31 August, 4-7 September 2025

Review by Carmen Nge

Fragments of Tuah (FT) is a spell-binding tour de force, a piece of documentary theatre that utterly engrossed and enraptured me from start to finish, lingering in my mind long after the house lights dimmed.

Conceived and directed by Mark Teh, in partnership with a small team — which includes long-time collaborators as well as newer ones — FT delves into the many stories about Hang Tuah, a figure who is no stranger to Malaysians. Structured as seven interconnected fragments, FT is not a show about the character of Tuah per se, but a kind of meta documentary theatre that unpacks the medium of storytelling itself via the figure of a national legend.

To achieve a degree of critical distance from the subject matter, audiences’ apprehension of Hang Tuah is mediated by a storyteller or penglipur lara, played by virtuoso performer Faiq Syazwan Kuhiri. In his multiple monologues, Faiq the storyteller never stops reminding us that he and his storied hero are not the same, despite their sharing racial and religious identity markers. And possibly a mustache.

When Faiq dons his paper samping and paper tanjak, and waves his paper keris, he is but a version of Hang Tuah materialized from books. Yet Faiq the content creator, who quit his job in media to become a full-time artist, is perhaps not as far removed from Hang Tuah the legend as we’d like to think. When Faiq shows us a snippet of his punk band Terrer’s music video Hang Loklaq, and tells us how they were trolled because of it, I wonder what brickbats Hang Tuah would have suffered if he had not dutifully killed his best friend Hang Jebat and, instead, chose a different path.

This strategy to friction national or Big History (the legend of Hang Tuah) with personal or small history (the storyteller/musician/regular guy that is Faiq) is a recurring trope in Teh’s works. It is a highly effective way to engage audiences on topics that might otherwise seem rather removed from our daily lives as ordinary folk.

The original songs that Faiq composed for FT also give us plenty of room to draw tangential connections between what is told on stage and what is sung to us, thereby enabling new interpretations of the Hang Tuah legend. For me, these songs imbue the show with a quality that elevates the aesthetics of documentary theatre, a form that is usually less interested with questions of aesthetics and more concerned with being truthful to the topic it tackles. This lofty goal can sometimes result in rather dry and overly didactic theatre, too wrapped up in its messaging to care about audience satisfaction. But not here.

Watching Faiq Syazwan Kuhiri is sublime. Having seen him in all his previous performances with Five Art Centre, his maturity as a performer is evident. He moves across the stage with sure-footed gravitas, every move deliberate, every gesture designed to draw us into his orbit. You can tell he is inherently comfortable in his penglipur lara skin and we are riveted.

At times he is circumspect and unassuming, directly addressing the audience in a convivial manner; at other times he has a larger-than-life presence, his gestures grand and expressive, as he moves with an unbridled kinetic force across the stage. There is also Faiq the actor and musician projected on paper screens, playing different parts while donning his digital creator hat, looking way more animated and facially expressive; this mediated two-dimensional charisma of his compels us, but it definitely plays second fiddle to his onstage one.

As the solo actor, accompanied by live musicians — O J Law on keyboard and Shariman Suhaime on electric guitar — Faiq commands our attention throughout the 80-minute show with a variety of impressive vocal techniques, which are suitably accentuated by the live instrumental music.

Faiq starts his performance in a seated kneeling pose, illuminated by a single pillar of light. He looks up, as if singing to a higher power. His pose is one of supplication, yet his meek and modest appearance contrasts with his incredibly hypnotic and powerfully resonant singing voice, which adeptly conveys an incredible range of emotions through pitch and tone.

Arguably, a storyteller’s most powerful instrument is his or her voice. A good story is nothing without a medium to convey it with and Faiq knows this well. When he speaks to us as himself — the boy from Perak, the son of lecturers, the globe-trotting performer, the man from the era of Internet 2.0 — Faiq alternates between charming and warm, relaxed and sincere, peppy and anxious.

When he tells the oft-told story of the Tuah vs. Jebat fight in Fragment 2: The Story, he uses a softer voice and speaks slower, in hushed tones. There is reverence in his diction, as well as emotional sincerity, coupled with a tincture of melancholy. His Gigi dan Lidah song is a fitting musical companion to the soundless P. Ramlee-as-Hang Tuah cinematic drama unfolding on screen; it is a high-pitched strain, plaintive and shot through with a palpable sense of the wretched tragedy. And when Jebat expires in Tuah’s arms, the slow, yet crisp trill of Faiq’s ukelele is all that remains.

When he reads from a lectern in Fragment 4: The Exhibition, Faiq adopts a serious, authoritative tone, with no trace of sentimentality or sarcasm. The exhibition refers to an actual Hang Tuah expo held at the Melaka International Trade Centre in 2024, which some of the FT team attended as part of their research. For this part of the show, Faiq stands next to Shariman, his back to the audience, while diagonally facing a giant screen centerstage. Due to this positioning, Faiq’s voice is curiously disembodied; here he is a news reader — a dispassionate conveyor of facts — or better yet, a professor at an academic conference. Ironically, not all the artifacts at the expo are as factually accurate or as scholarly as they seem.

As a work of documentary theatre — a form that relies on the use of primary sources such as interviews, archival documents, and personal testimonies rather than fictional texts, to explore a theme or real-life event — FT lives in the interstices of fabrication, fact, and fiction. If, in previous productions, Teh uses primary materials to lend credibility to his subject matter, here, in FT, some of these materials — notably the keris found in Okinawa said to be Hang Tuah’s — are the subject of interrogation and later exposed as unreliable. But this exposure is effected with the utmost delicacy: no cries for accountability or Socratic questioning à la Fahmi Reza in Teh’s previous production, A Notional History. In our post-truth era of fake news, deep fakes, counternarratives and echo chambers, the quest for truth is perhaps a futile one.

What makes FT so incredibly absorbing and enthralling has chiefly to do with the immersive quality of the performance space. The set of FT is a conceptually strong assemblage of physical, digital, and virtual materials, painstakingly handcrafted by production designer Wong Tay Sy, who worked closely with Syamsul Azhar — who doubles as lighting and multimedia designer — and his colleague Bryan Chang. With the aid of delicate and ephemeral materials such as paper and light, Wong and Syam have lovingly built a world worthy of the weight and aesthetics of storytelling.

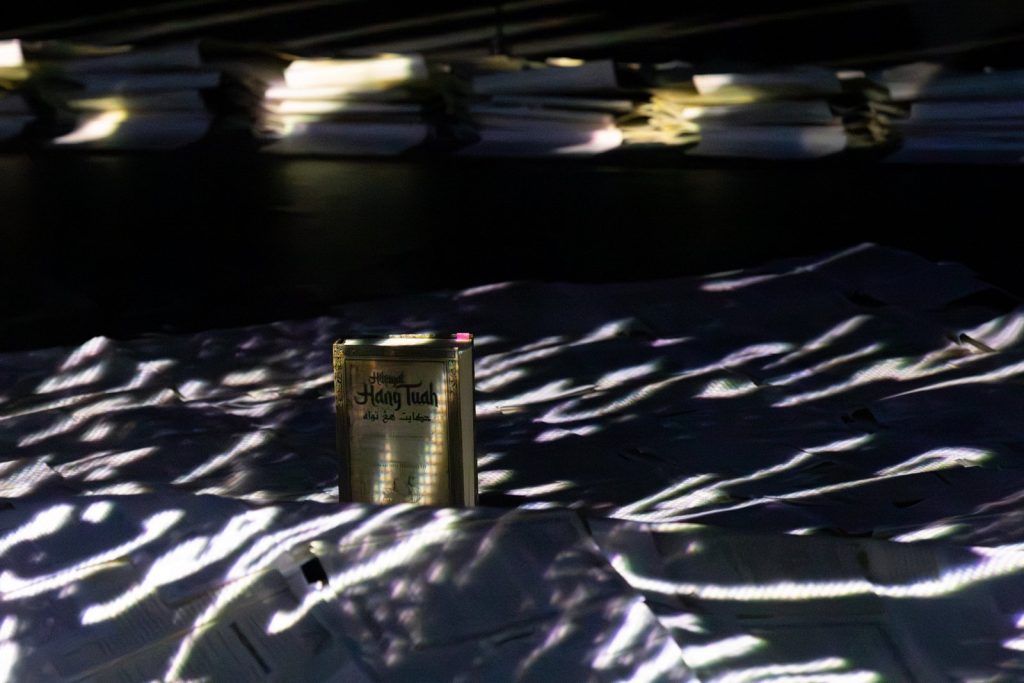

Remarkably, all the props we see on stage are born of books, and this is by design. You see, Mark Teh has a fetish for books. He has been using books as props for at least a decade, if not more. But it is not just any book that strikes his fancy. He has a sustained appetite for old, weighty tomes that are plucked from the jaws of history and preferably out of print. Mark’s keenness for the contents of said books is well-matched with Wong’s felicity in deconstructing them and imagining new geographies of place via the materiality of paper and the semiotics of the printed word. The pages of a book are delicate but when bound together, they have heft and can cast shadows. They afford material density to the immaterial ideas within.

Books are both artifact and catalyst in FT. Books can be trusted but they are not all trustworthy. They are repositories of knowledge, but the perspectives they contain are not infallible; their authors proffer entry points into a zeitgeist, yet how we make sense of this history is out of their hands. From the performance, I learnt that the Hikayat Hang Tuah — the foundational text that Teh’s collaborators had to read and discuss to prepare to make FT — has no known author(s) and is likely a synthesis of stories from multiple and indeterminate oral and written sources.

Books are windows into new realms of ideas and stories, but they are also a bulwark against obsolescence. Inasmuch as they help to fortify our opinions and perspectives, they can also be walls erected to imprison us in them. Wong plays with these ideas in her production design by weaving pages of books together into giant tapestries that also function as screens for Syam’s multimedia projections.

Just as hikayat (story) is not hakikat (fact), Hang Tuah as we know him today is an open source figure, an intangible asset, a legend who is freely accessible in the public domain, yet also available for modifications and upgrades. A story without end. Add infinitum.

And what of Tuah the man? Can heroes die if their continued existence is of our making and not theirs? ‘Takkan Melayu hilang di dunia’ is a saying often (erroneously) attributed to Hang Tuah and etched forever on Waveney Jenkins’ bronze relief sculpture of him at the National Museum. What if this particular Malay man wants to hilang or wander off? Will he be allowed to shrug off the shackles of ethno-nationalistic expectation and feudal subservience, and chart his own path into the unknown?

The last two chapters of the Hikayat appear to grapple with these questions, albeit in a cryptic manner using dreams and parables. In the post-show discussion, Teh tells us that most people don’t talk about the final chapters. And for good reason. When Faiq read us excerpts of these chapters, I was struck by how mystical they sound, almost Sufi-like. The monarch is close to death, and Tuah is trying to make sense of his place in the world. It is now Tuah’s turn to tell a story, one so arcane and inscrutable it will never survive the TikTok generation.

The final fragment of FT is an audiovisual spectacle that will surely go down in Malaysian theatre history for being indelibly evocative and brimming with sensoriality. This haunting closing scene lives in my mind even until today.

At the very start of the show, the stage is an eye-catching topography made up of books, irradiated by pillars of light to resemble little islands spread across the Malay Archipelago, from which the story of Tuah emerges. Towards the end, these islands have been submerged beneath two large burial shrouds made from a tapestry of book leaves. Fittingly, the show begins and ends in darkness — just as a story can transpire from the unfathomable depths of human creation, a story can easily fizzle away like sea foam, dispersed by the tides of time.

As the notes of the final song, Kan Ku Hilang, gradually merge with the gentle sounds of waves lapping along the humanmade paper shorelines, we see animated Jawi script emerging from the woven pages, little flecks of light dancing, converging and reconstituting, ebbing and flowing, every now and again disappearing, yet somehow conspicuously alive.

Carmen Nge is an occasional writer and arts enthusiast; she is currently an assistant professor at the Faculty of Creative Industries, Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman (UTAR).

Photos by Pam Lim and Meshalini Muniandy, courtesy of Five Arts Centre.