- Views3754

- Likes1

A Notional History

Five Arts Centre

GMBB Kuala Lumpur

23-26 June 2022

review by Carmen Nge

A nation’s history is the bedrock upon which a national identity germinates; its power lies in its immutability, its unshakeable persistence over time. Yet even bedrocks can weather and erode, their evolution detectable through small cracks and deep striations.

Directed by Mark Teh, Five Arts Centre’s latest piece of theatre, A Notional History (ANH), tackles this highly charged subject matter by excavating how history has been constructed and reconstructed by those in power, endlessly made and remade according to shifting political wills, and, in our present digital age, is inescapably mediated.

ANH revolves around one particular fissure in the Malaysian historical bedrock: the Malayan Communist Party (MCP). Vilified for decades by the Japanese, British, and Malayan authorities, the MCP is the bogeyman that never quits. Everything we learnt in schools communicated a simple, seemingly incontrovertible fact: all MCP members are Chinese, godless, and bloodthirsty killers.

ANH counters this factoid with an equally simple question: what if our history books are not entirely true?

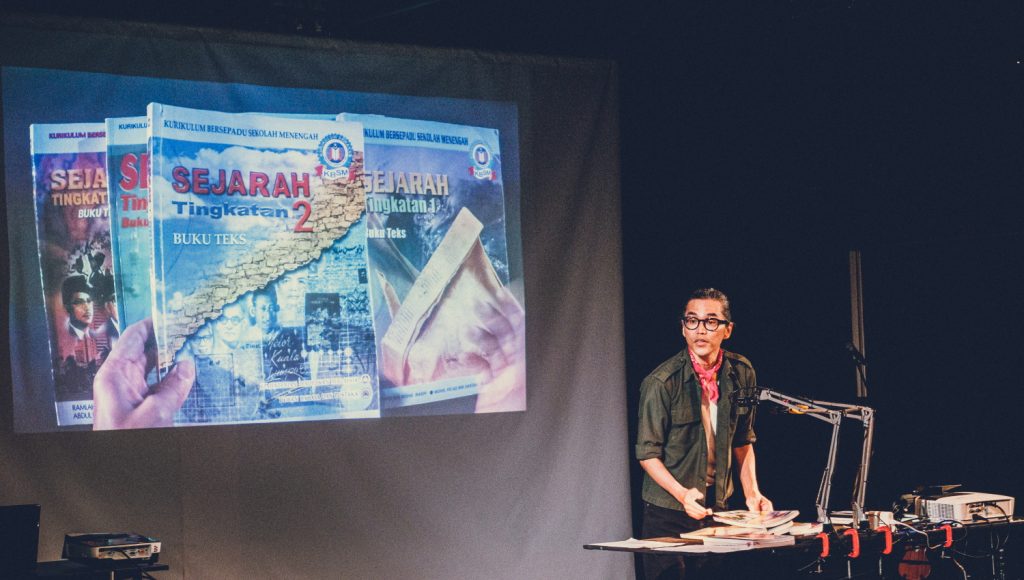

To answer this question, performers Rahmah Pauzi, Faiq Syazwan Kuhiri and Fahmi Reza employed a range of tools that are familiar to documentary theatre practitioners: archival video and audio footage; published textual materials in the form of history textbooks, examination papers and newspaper clippings; and a slew of analog and digital images, from old photographs to screenshots of social media posts and comments.

These tools were curated and consolidated in service of a piquant historical counterpoint: MCP members were not only Chinese—some were Malay and Muslim, and members felt a patriotic duty to take up arms to fight and, if necessary, to kill for an emancipated Malaya, free from Japanese and British shackles.

Unlike their earlier play, Baling, which also navigated similar historical terrain, the performers in ANH did not take on the role of luminaries such as Chin Peng or Tunku Abdul Rahman. This time they let their tools do the talking, and the MCP members to speak for themselves.

Thanks to the availability of raw footage from interviews that Fahmi Reza and his collaborators conducted with MCP members for his unfinished 2008 documentary, Revolusi 48, video journalist and documentary maker Rahmah Pauzi was able to adeptly select snippets with which to craft a narrative of the MCP told in their own words. Somber and occasionally witty recollections and perspicacious wisdom permeate these wonderful vignettes of lives lived with simple conviction, guided by enduring principles of equality, freedom, and belonging.

Yet these are not youthful MCP soldiers in their prime but a slow-moving, doddering bunch, and we are hard-pressed to see them as villains. Their senescence is a stark reminder of how history must be revisited and revised every so often if we are to continue to draw meaning and shape our national trajectories upon it.

As their stories unfolded on screen, I could not help but notice the remarkable juxtaposition of generations in the performance space: geriatric MCP members projected in 2D—larger than life and in full colour—provided the backdrop against which Malaysian performers in their 40s and 30s narrated their own intersecting stories of selfhood and kinship. Empowered by decades of search and research, and emboldened by an ensemble with a strong sense of camaraderie honed over years of working closely together, ANH is the very embodiment of the history it seeks to reappraise.

What was novel and compelling about ANH, however, was not just the team’s affecting performances and masterful curation of documents old and new, but rather their ability to entice audiences to watch history being spontaneously made and remade via live chalk drawings. Production designer Wong Tay Sy’s reimagination of the performance space as a chalkboard—reminiscent of the ones some of us encountered as schoolchildren—was a strategic move designed to involve us in the process of making meaning from the flows of information conveyed via mediated screens and archival material. The stage floor thus served as an additional horizontal plane upon which to enact graphical interpretations and permutations of official textual history. Interestingly, it also afforded us an opportunity to see Fahmi Reza doing what we know him best for, but hardly ever witness on stage: drawing.

For those seated on the floor, who were in closest proximity to the performers, watching the drawings take shape took on an almost hypnotic quality. These were not the doodles and scribbles from our schooldays, created to while away the time or to keep boredom at bay. They were markings imbued with intensity and intent. Throughout the 75-min show, all three performers would make their mark on the floor; Faiq even rolled around in chalk dust, contorting his torso and limbs to draw multiple, overlapping outlines of his own head and body.

Rahmah chalked outlines of history textbooks that served as photo frames within which Fahmi Reza sketched a diverse array of human heads—each with incomplete faces but some with distinguishable cultural markers. A few of these drawings resembled the MCP talking heads in the videos; others reminded me of IC or passport photos, due to the way the heads were composed and framed. By the end of the show, many of these faces would be marred or even rubbed out by the soles of the performers’ bare feet, a painful metaphor for how history’s victors often ride roughshod over its losers.

Certain signs and symbols had more overt inferences. The Union Jack, which was adjacent to a large drawing of a soldier wielding a gun, shared floor space with a large map of Malaysia. Most notably, what started out as a drawing of a crescent moon and star later morphed into that of a hammer and sickle. Audiences who paid careful attention were rewarded with such unanticipated moments of transmogrification.

But the visual and spatial design was by no means the most enthralling aspect of ANH. For this reviewer at least, the piece de resistance of the show had to be the music, transmitted so mesmerically via Faiq’s voice and his trusty ukulele, often considered to be the people’s musical instrument due to its size, affordability, and folksy appeal. Music gave audiences a potent way to access the dimensions of historical space and time.

With his opening song, armed with a deep and mellifluous voice, Faiq transported us into the jungles where the MCP sought refuge for many decades; the song lyrics sparred and parried with the realities of dementia and death, offering new layers of apprehension and exposition of life lived in hiding or exile. Music was a big part of MCP communal life; songs buoyed their spirits and singing in unison forged a strong sense of solidarity. More importantly, as the video archives attest, songs somehow manage to resist forgetfulness; music endures even when memory does not. Faiq’s songs and plaintive singing paid tribute to this axiom.

Music was also able to effectively immerse us in time, inducing rousing emotions and conceiving an atmosphere of unease. During a World War Two scene in ANH, Faiq filled the room with haunting baritone strains of a war elegy and the strum of his ukulele throbbed in concert with archival footage of war planes and bombs being dropped. His resonant singing was joined in harmony by stage manager Alison Khor, who unexpectedly entered the vocal fray with a powerful, resounding wail, which was highly evocative of air raid sirens.

Such diverse auditory-artistic interventions infused ANH with sensory power and poetic nuances, without which it could have easily devolved into a tedious, intellectual exercise. Through their kinetic use of space, sound, and simulacra, the performers of ANH deftly unmoored our past from its dry and inert textual authority, prodding us to re-examine our (mis)conceptions and inviting us to consider an alternative notion of history.

But how are we to redress Malaysian history’s willful gaps and inadvertent fault lines? ANH ends with a surprisingly evocative and richly symbolic multimedia manoeuvre engineered by Syamsul Azhar, the lighting and media designer in the ANH team. Deftly overlaying still and moving digital images of the unsung and forgotten heroes of history onto actual history textbook pages that were projected onscreen, Syamsul presented us with a technologically prescient solution that shimmered with the promise of co-existence.

As Rahmah turned the pages of our history textbook, we witnessed entrenched official narratives share space with newly unearthed subterranean histories; instead of mugshots of Malaysia’s usual political suspects, we saw faces of MCP members, activists, and even those of artists and performers. As the textbook came to a close, the final few pages were fittingly blank.

This is history as it can and should be: alive, vital, open-ended, and as we make it.

All photos by Bryan Chang, provided by Five Arts Centre.

Carmen Nge is a writer and arts enthusiast; she is currently an assistant professor at the Faculty of Creative Industries, Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman (UTAR).