- Views16529

- Likes4

Baling

Produced by Five Arts Centre

30 March – 3 April 2016

Kotak, Five Arts Centre, Taman Tun Dr Ismail

REVIEW BY Carmen Nge

It is rare to be privy to a play’s evolution, and even rarer still when the same person helms its many iterations. In the past decade, Mark Teh’s ostensible obsession with the 1955 Baling talks–a significant event in Malaysian history–has proven fruitful for theatre audiences.

From the usual crowd of Klang Valley theatregoers to the not-so usual crowds at futsal courts and university classrooms, and most recently to new audiences in South Korea, Japan, India and the United Arab Emirates, Five Arts Centre has toured Teh’s creative experiment far and wide, almost as a paean to the travelling theatre troupes of a bygone era.

Having witnessed two prior iterations of the play in 2005 and 2008, I expected to feel a sense of déjà vu when watching the latest production of Baling but there was none to be had. This 2016 version of the familiar tale bore very little resemblance to its predecessors.

For one, the pace of the current version of Baling was exceedingly measured. The play was divided into scenes or sessions; each unfolded in well-designed blocks of time and space that were unified by a common thread: movement. As the actors moved, the audiences had to move as well. The two-storey shoplot that houses Five Arts Centre lent itself well to this poly-perspectival experience of mobility.

Each space was sufficiently different to warrant a new way of viewing and experiencing. For night performances, the first session of Baling took place out in the open. The outdoor screening of a newsreel of the Baling talks, taken from the British archives, was a gentle nod to pre-Independence Malaya, where such public screenings were the norm. As I stood watching the black and white footage projected onto the exterior of the shoplot, I spied some customers and many workers at the neighbouring mamak + vape hangout stealing a few peeks.

From the roofless open air space, audiences were then ushered through a narrow staircase up to the second floor and into an extremely constricted square room, where they had to sit on the floor. Performers claimed one half of the space and the audience had to make do with the remaining half. Close proximity to the performers helped to generate a good deal of discomfort for the audience; the heat and the uneven circulation of air from the stand fans around the room exacerbated the feeling of unease and disorientation. I imagined this must have been what it felt like to be a member of the Malayan citizenry, waiting in the heat outside the schoolhouse where the actual Baling talks took place.

Audiences were then directed downstairs once more for all subsequent sessions, which took place in the air-conditioned comfort of Five Arts Centre’s black box space on the ground floor – but audiences were never allowed to stay in one spot for too long. Performers kept forming and reforming new bounded spaces within the black box, and audiences were forced to re-align themselves within these new boundaries. It was as if the territorial negotiations born out of Malaysia’s colonial past lived on in the present moment in an abstracted, yet highly palpable form. The corporeal movements of the audiences also reflected the geo-political movements of our young nation: most notably, the 1963 formation of Malaysia and the later separation of Singapore and Brunei.

The constant shifting was a big ask for audiences new to Five Arts Centre’s theatrical strategies but for those who have seen previous plays by the company, like Family (1998) or 2 Minute Solos (2013), moving around is nothing new. Passivity and complacency are not words common to the Five Arts lexicon and each session required audiences to physically re-articulate their relationship to the performance space. Shifting their bodies also meant shifting their perspectives about the play and its meanings. On a symbolic level, the intermittent movement also reminded me of members of the Communist Party of Malaya during the Emergency period: always on the move, always on the run, chasing an ideal that would always be beyond their reach.

The construction, deconstruction and reconstruction of space, and their attendant disruption of the usual passive complacency of the audience, are the lynchpins of this 2016 staging of Baling. If, before, Baling Membaling (2005) was about the movement of key figures (Tunku Abdul Rahman and Chin Peng) at the Baling talks, then this iteration foregrounds the movement of the people who were kept out and who were not privy to the actual discussions.

I remember the explosive energy and kinetically engaging performances of the three non-actors in Baling Membaling; that first staging clearly foregrounded the actors and their relationship to each other in a riotous and raw amalgamation of text, bodies and sound. For this production, the acting is polished and the energy is disciplined, extremely focused on the articulation of the text of the Baling talks.

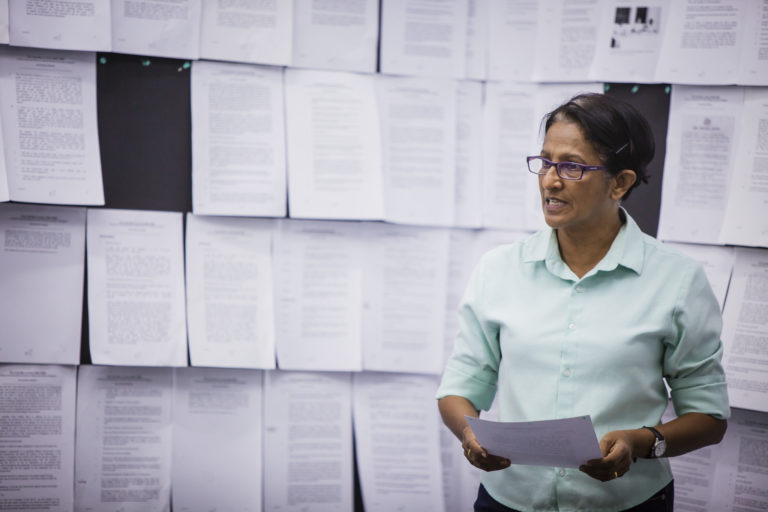

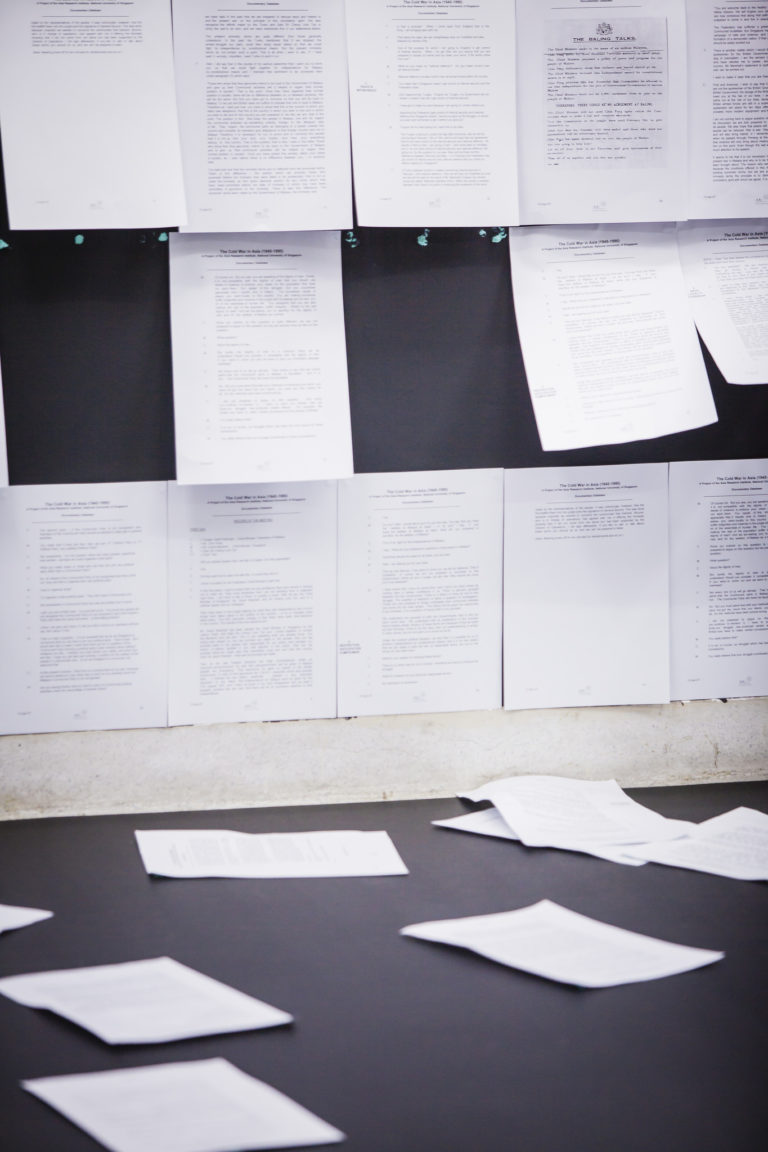

The weight and significance of history, as captured and transmitted in the form of texts, came to prominence in the inventive ways in which words were packaged and presented in diverse forms in Baling. They appeared on pieces of white paper tacked onto walls like flimsy tiles that were later ripped from their weak moorings; they appeared on facsimiles of posters and news clippings, and floated, stark white projections against black backdrops; they resided in books that were used to demarcate space and sculpted by the performers into three-dimensional images.

With each staging of the Baling talks, director Mark Teh’s fidelity to the archives of history has become more pronounced, and he eschews the amorphousness of the creative process to latch onto the simulacra of the document. But in this staging, Teh’s relationship to the text is emboldened by the radical production design of Wong Tay Sy, who manages to make words take shape in ways that challenge the perspicuity of the text. Words became text became objects became space became images in Baling; and through the actors, the performative and the textual become inextricable.

Interestingly, all four actors broke away from the text of the Baling talks at different points of the 100-minute long performance, to play themselves. These interludes were opportunities for the actors to share their personal views and/or relationship to the history that was being performed in the play. The Baling talks, in these instances, were being “talked about” in a surreal form of meta-commentary by the same people who would then continue to read and enact them.

Younger audiences unfamiliar with the Baling talks in particular, and Malaysian history in general, would welcome these narrative breaks because they provided an entry point into the dense and, sometimes, confusing transcripts. Importantly, the actors also provided context for audiences, and one of them, Fahmi Fadzil, connected past events to contemporary ones in very cogent ways.

The final interlude, by Imri Nasution, presented a most fitting end to a play that never endorsed any one perspective of the Baling talks, but instead constantly expected us to listen, watch and question the unfolding of a critical juncture in our history. In this final session, the spectre of Chin Peng–who had been visualized many a time in Baling as a floating head in the black box space–was now presented as a talking head.

In this last known video interview with the man the British, at one time, considered “public enemy No. 1” we see a very old man, who stares blinkingly off-camera and who is fairly taciturn. The only time he says more than a few words is when he laments being unable to return to Malaysia, to die there and to be buried there. His final wish would, as history would show, never be granted by the Malaysian government, making this final video all the more moving and poignant.

After almost 97-minutes of being tasked to engage with history textually and cerebrally, when watching the video I found myself surrendering to emotions. In the end, no dispassionate and cerebral apprehension of the text could evacuate my need to feel something for this period in our nation’s history, a need that the video interview marginally provided, unresolved and unfulfilling though it may have been.

Carmen Nge is a writer and arts enthusiast; she is currently an assistant professor at the Faculty of Creative Industries, Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman (UTAR).

Photos by Wong Horng Yih, courtesy of Five Arts Centre.