- Views5038

- Likes0

Dash

Created and presented by Ho Rui An

22-23 September 2017

Kotak, Five Arts Centre, Taman Tun Dr Ismail

Review by See Tshiung Han

Our world is crisscrossed by lines. In 2016, a group show in Brisbane called Frontier Imaginaries: The Life of Lines explored our relationship with them, staging dialogues about topics from “the history of the ‘Brisbane Line’ to ecological lines such as the Great Barrier Reef, current urban/rural and digital divides, and [sea] borders with neighbouring pacific nations to the north.”

Dash, which had a two-night run at Kotak, Five Arts Centre, in September, was commissioned for Frontier Imaginaries, and before coming to Malaysia it was also performed in Berlin and London.

For Malaysian audiences, Dash looked like a tough sell. Singaporean artist Ho Rui An, who wrote and performed the work, isn’t known in the country. Dash is a performance-lecture and very few of those have been available to Malaysians either: off the top of my head, only Five Arts Centre’s Gostan Forward in 2009 and a performance-lecture of Hamlet in 2015. And yet, Five Arts was able to fill the house on opening night.

If Dash could be said to be about a line, perhaps it is the line between moving and not moving. Such a line may seem insignificant but it can make a difference if you are, for example, trying to cross the road. This is sometimes called a frame of reference. Imagine Persons A and B are in a car, and the car is moving at 40 km/hour. If Person A looks at Person B, he will appear to be not moving. But to a third person, Person C, standing at a pedestrian crossing as the car drives past, Persons A and B will appear to be moving quite fast indeed.

If the line between moving and not moving is less clear than we think, then so is the line between moving slowly and quickly. Ho himself seems to be gathering speed. In 2015, he was interviewed by global art impresarios Hans Ulrich Obrist and Simon Castets, for the first issue of KALEIDOSCOPE Asia.

In the interview, Ho tells Obrist and Castets, “My most formative encounters happened in [cinema, literature, anthropology, philosophy, cultural studies and media theory], with contemporary art being more of the site to negotiate and collide these different influences.” A collision of different fields of study is a good way to think of Dash, which has a freewheeling sense to it: Ho moves from Star Trek to horizon scanning to Western movies, from Marina Bay Sands to migrant labour crisis.

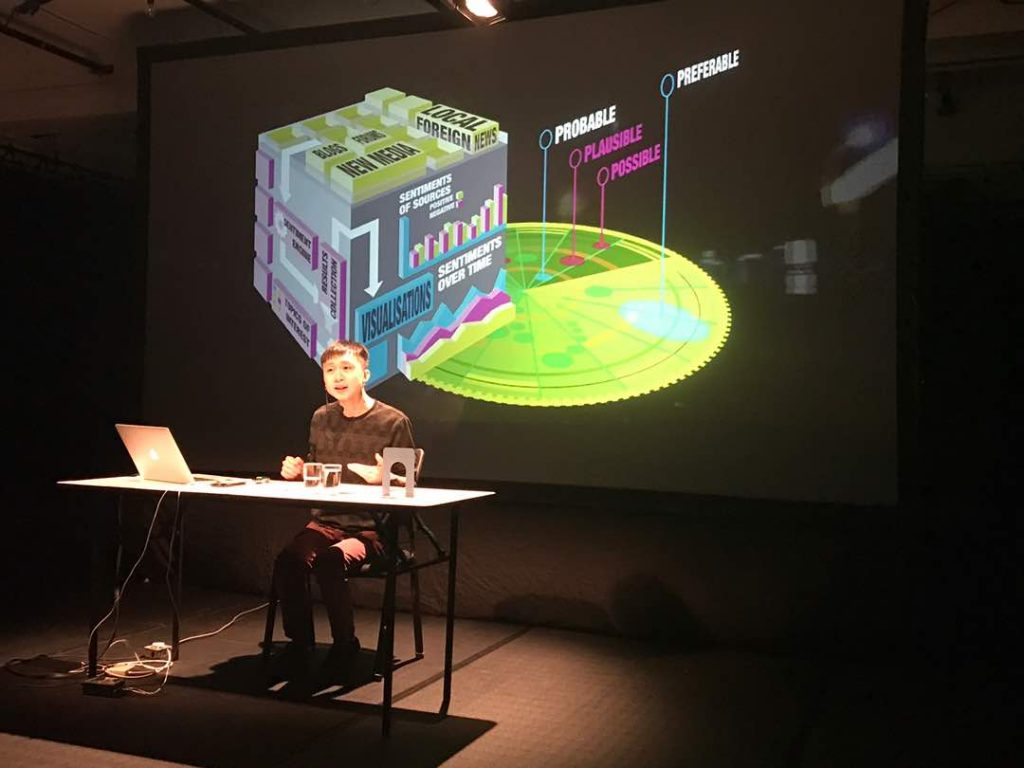

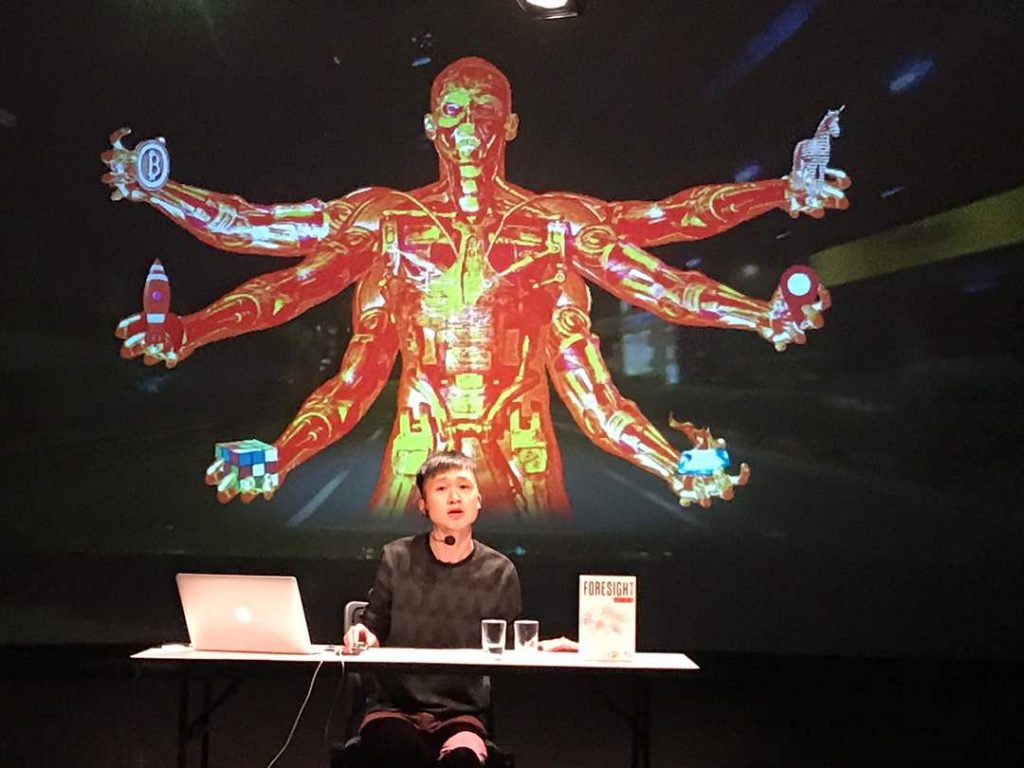

Ho hits all of these topics seated at a desk throughout the whole performance, moving to queue up the next video on the laptop in front of him with the projection screen behind him. His videos were slickly produced, not your usual iMovie fare. At one point, one video played in the foreground while another video played in the background. But the staging is very flat, intentionally so. Ho wants you to pay more attention to the words and images.

Dash uses a 2012 crash between a Ferrari and a taxi to discuss how the Singapore government deals with crisis. Apparently, Singapore has been spending money trying to anticipate crises, using a form of data analysis called horizon scanning that allows the government to “identify potential threats, risks, emerging issues and opportunities.”

The show is also about “moving forward,” moving on from a traumatic moment experienced as a society, as well as being propelled forward in time and space. At the same time, it’s about the inability to move forward. Obstacles lie in our path, but we cannot see them clearly as we move towards them.

It’s also about “moving into.” At the beginning of the show, we are an onlooker to a fatal crash. At the end, we are in a crash. Dashcam footage from the Ferrari or taxi doesn’t seem to exist, so Ho shows us footage from another crash, one of many that can be found online. In doing so, he invites us to consider this shift in viewpoint, especially when thinking about the future.

One might gather that, for Ho, this whole enterprise of anticipating the future is, for lack of a better word, quixotic. “And how exactly,” Ho says, “can one possibly train for this impossible undertaking of anticipating surprise or, if I may, anticipating one’s failure to fully anticipate?” He never comes out and says that Singapore’s horizon scanning program is a fool’s errand, but the thought might occur to you if you read between the lines.

Ho doesn’t make it easy for the viewer to discern his meaning. His writing is elliptical. Speeding, Ho says, is to turn “speed into a thing to be relished in itself.” After watching the viral video of the 2012 crash, he tells us that a viewer is left “with the posthumous sense of having missed the moment of trauma.” Perhaps the viewer will remember these ambiguities more vividly than the parts about Star Trek or black swans – but I doubt it.

Though unclear on the specifics, Ho is clear about the generics. The 2012 crash is a symptom not of an impending crisis, but a crisis in progress. Singapore’s horizon scanning program, designed to detect so-called weak signals and mitigate their growth into full-blown crisis, failed to pick up on this one because of its imperative that a country has to keep growing, has to keep moving forward. It has no time to consider the exploitation of “one million or so” migrant labourers, for example.

In bringing this to our attention, what would Ho have us do?

He would have us look before we move.

“You’re never told what’s true and what isn’t true,” the filmmaker Robert Altman says about Kurosawa’s Rashomon, “which leads you to the proper conclusion that it is all true and none of it’s true. So it becomes a poem that cracks this visual thing in our minds. That if we see it, it must be a fact.”

In unpacking some of what we see around us, Ho tries to crack the visual thing in our minds, but he only succeeds in scratching it. Perhaps repeat viewings of Dash are needed to get cracking. For such a short run, all we can do is rubberneck the debris and keep driving.

SEE Tshiung Han is a writer and editor based in KL.

All photos courtesy of Five Arts Centre.